HISTORY OF THE NATIVE AMERICAN

DOGS

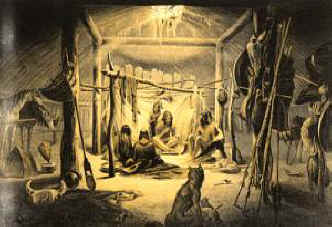

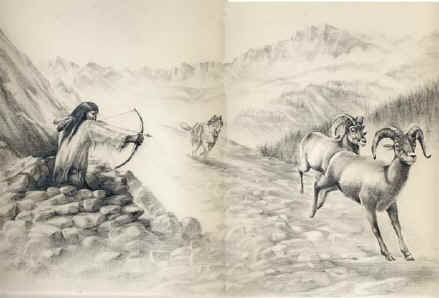

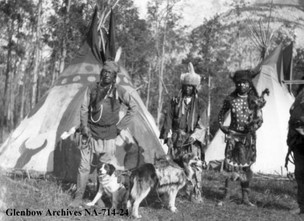

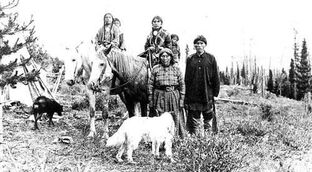

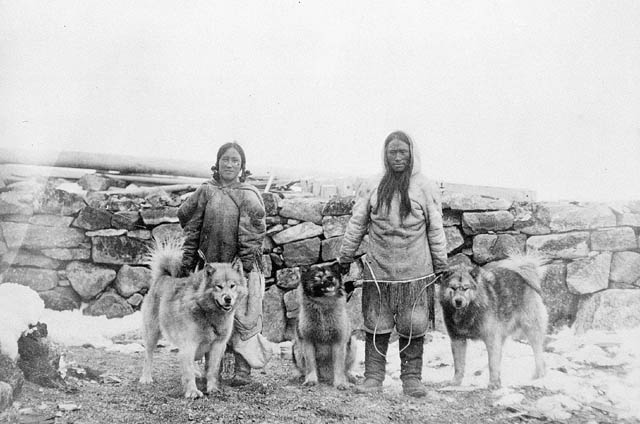

The Native Americans taught their dogs how to fish and hunt. The Pacific Northwest Indians used their dogs to hunt bear, elk, deer, mountain sheep and water fowl. Specially trained dogs would drive elk and deer into snares. The Inuit dog helped in the hunting of seals and polar bears. They were very skilled hunters and very courageous and protective of their owners and their families.

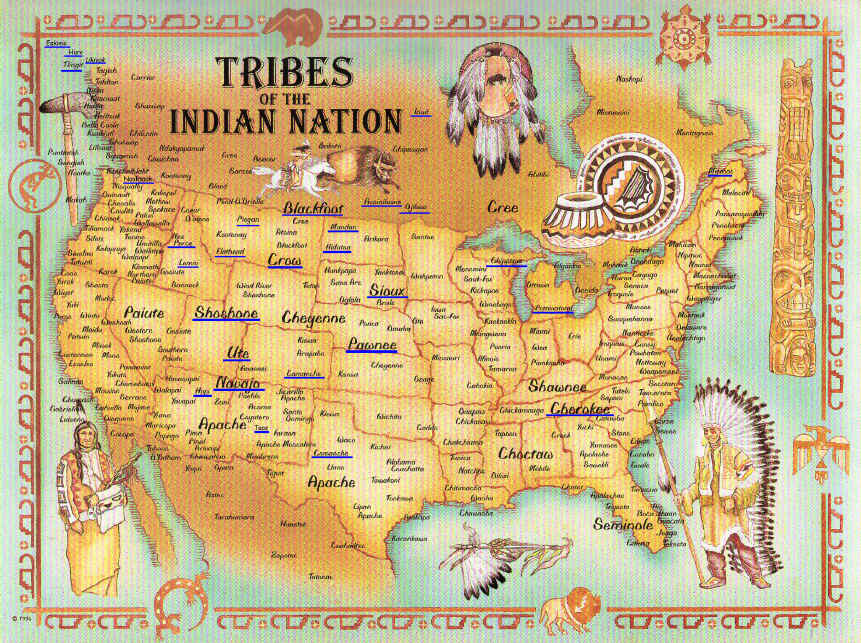

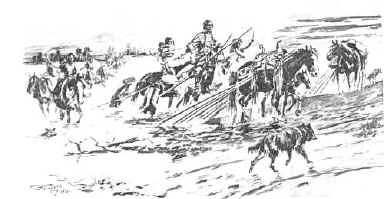

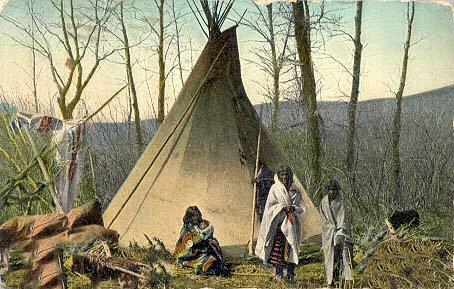

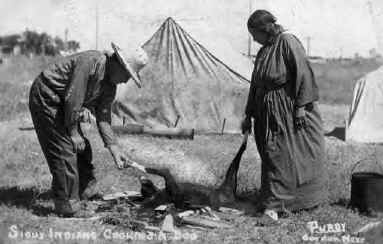

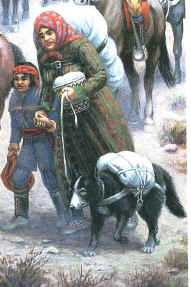

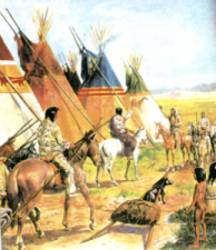

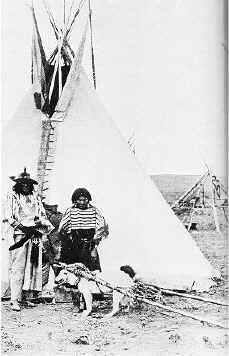

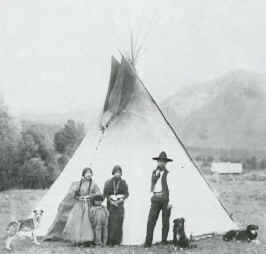

From the far most Northwestern reaches of the Aleutian Islands to the Southern most tip of present day Mexico, dogs have played a vital role in the lives and cultures of the First Americans. As transportation for family belongings when following their food supply, in the hunt for food needed to help feed their families, being faithful watch dogs, and even performing for the "Wild" Buffalo Bill Shows, the Native Americans depended on their dogs to assist them in anyway they might need. In 1719 Pachot observed that dogs, of which the Ottawa's had numerous... regarded their dogs as a precious commodity as white man regarded sheep. When villagers became ill, dog meat was the most medicinal healing meat there was to be found.

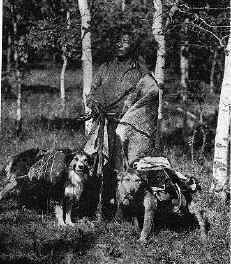

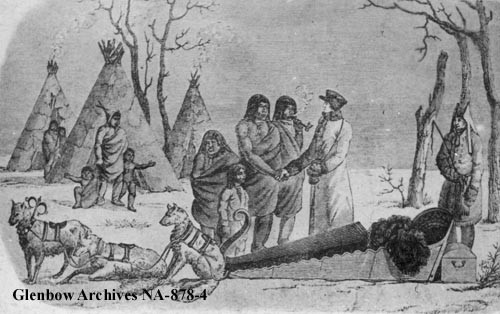

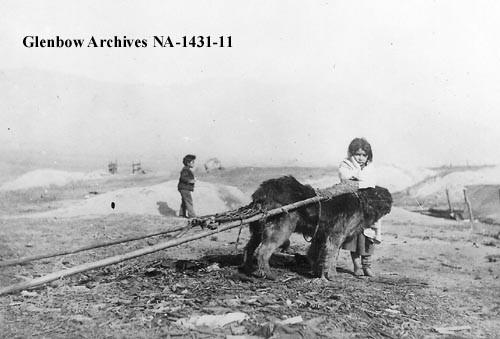

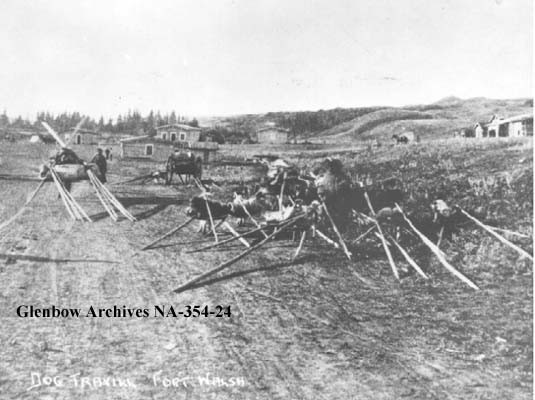

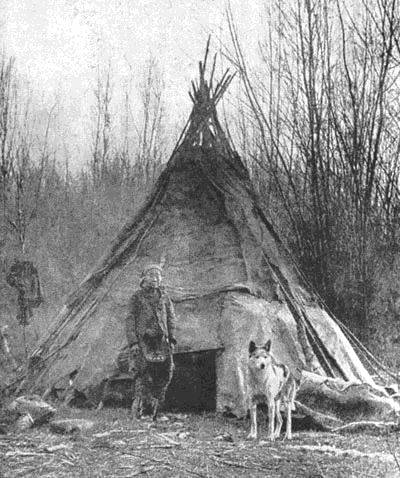

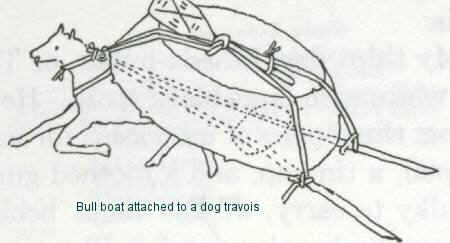

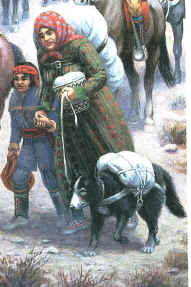

I 1765 the Hidatsa was discovered by whites and documentation reveals that the Hidatsa peoples still used the dogs and the dog travois as a mode of transportation, not horses. In 1804 Lewis and Clark discovered them still using dogs as a sole means of transportation. The Lemhi Shoshone were discovered in the mid 1800's as still using dogs for utility work and beasts of burden...no horses were owned by these people. Each family had upwards of 30 dogs each. The majority of the Lemhi had been killed off by European disease and only a handful of these Shoshones' remained. The Lemhi loved their dogs so much that when a family member died their favorite dog was killed and buried with the individual.

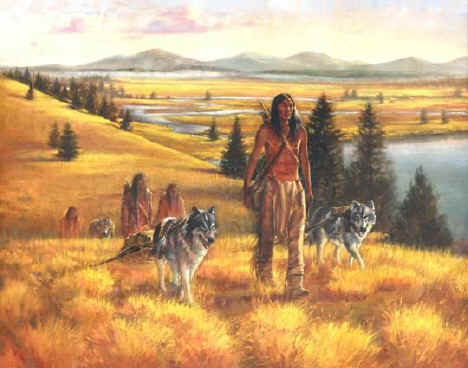

Sir John Richardson, writing in 1829, observed that "the resemblance between the North American wolves and the domestic dog of the Indians is so great that the size and strength of the wolf seems to be the only difference. I have more than once mistaken a band of wolves for the dogs of a party of Indians; and the howl of the animals of both species is prolonged so exactly in the same key that even the practiced ear of the Indian fails at times to discriminate between them."

http://www.adogbreed.com/history.php

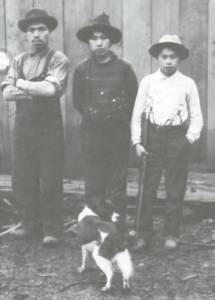

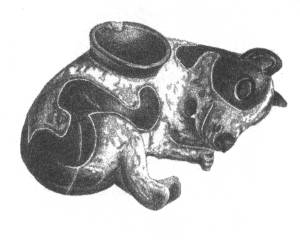

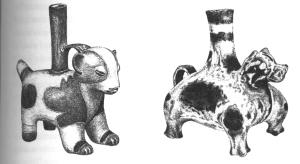

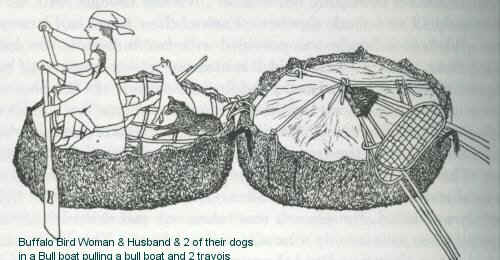

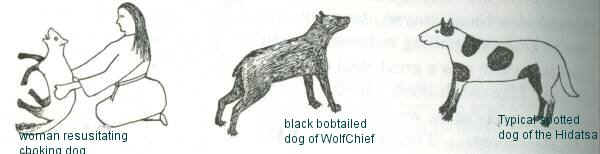

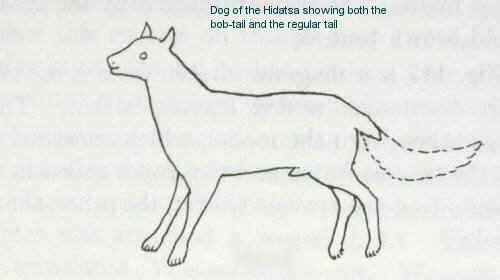

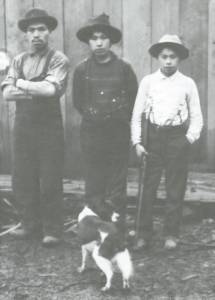

IN THE HIDATSA INDIAN CULTURE, THE WOMEN WERE IN CHARGE OF THE BREEDING AND TRAINING OF THE DOGS. A FAMOUS HIDATSA WOMAN BUFFALO BIRD WOMAN, WHO LIVED DURING THE 1800'S, BRED FOR TAILESS DOGS AND THE BROKEN PATTERNED DOGS, OR "SPIRIT DOGS" AS THE NATIVE AMERICANS CALLED THEM. MAJESTIC VIEW KENNELS HAS BEEN HONORED AND BLESSED TO HAVE TWO BROKEN PATTERNED, TAIL LESS NATIVE AMERICAN DOGS BORN. MAJESTIC VIEW'S HIDATSA BOBTAIL IS CURRENTLY A PRIME BEEDING SIRE HERE AT MAJESTIC VIEW.

From the far most Northwestern reaches of the Aleutian Islands to the Southern most tip of present day Mexico, dogs have played a vital role in the lives and cultures of the First Americans. As transportation for family belongings when following their food supply, in the hunt for food needed to help feed their families, being faithful watch dogs, and even performing for the "Wild" Buffalo Bill Shows, the Native Americans depended on their dogs to assist them in anyway they might need. In 1719 Pachot observed that dogs, of which the Ottawa's had numerous... regarded their dogs as a precious commodity as white man regarded sheep. When villagers became ill, dog meat was the most medicinal healing meat there was to be found.

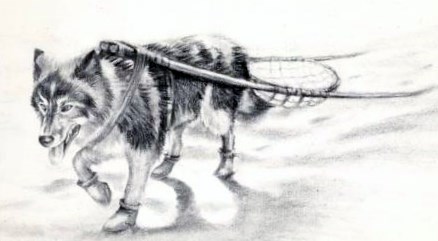

I 1765 the Hidatsa was discovered by whites and documentation reveals that the Hidatsa peoples still used the dogs and the dog travois as a mode of transportation, not horses. In 1804 Lewis and Clark discovered them still using dogs as a sole means of transportation. The Lemhi Shoshone were discovered in the mid 1800's as still using dogs for utility work and beasts of burden...no horses were owned by these people. Each family had upwards of 30 dogs each. The majority of the Lemhi had been killed off by European disease and only a handful of these Shoshones' remained. The Lemhi loved their dogs so much that when a family member died their favorite dog was killed and buried with the individual.

Sir John Richardson, writing in 1829, observed that "the resemblance between the North American wolves and the domestic dog of the Indians is so great that the size and strength of the wolf seems to be the only difference. I have more than once mistaken a band of wolves for the dogs of a party of Indians; and the howl of the animals of both species is prolonged so exactly in the same key that even the practiced ear of the Indian fails at times to discriminate between them."

http://www.adogbreed.com/history.php

IN THE HIDATSA INDIAN CULTURE, THE WOMEN WERE IN CHARGE OF THE BREEDING AND TRAINING OF THE DOGS. A FAMOUS HIDATSA WOMAN BUFFALO BIRD WOMAN, WHO LIVED DURING THE 1800'S, BRED FOR TAILESS DOGS AND THE BROKEN PATTERNED DOGS, OR "SPIRIT DOGS" AS THE NATIVE AMERICANS CALLED THEM. MAJESTIC VIEW KENNELS HAS BEEN HONORED AND BLESSED TO HAVE TWO BROKEN PATTERNED, TAIL LESS NATIVE AMERICAN DOGS BORN. MAJESTIC VIEW'S HIDATSA BOBTAIL IS CURRENTLY A PRIME BEEDING SIRE HERE AT MAJESTIC VIEW.

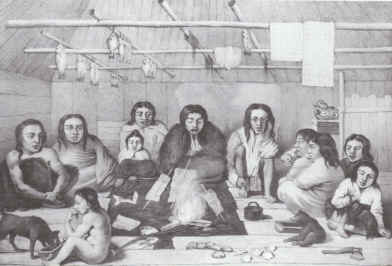

NATIVE AMERICANS OF THE GREAT LAKES REGION

The spirits who lived at the bottom of the Great Lakes required sacrifices of certain colored dogs bound with legs and muzzles tied and thrown into the water so the angry gods would be appeased and fishing and traveling on the waters would be good and safe for the peoples. In 1709 it was observed that the tribes of the Great Lakes region would leave their villages nestled along the banks of rivers and lakes to go far inland to winter with their numerous dogs. These dogs are of the large sort, with bodies of a wolf and heads and ears of those of a fox.The Ojibwa Indians of the Great Lakes region harvested maple sap in the spring before heading back to their summer villages along the banks of rivers and lakes. Maple sugar and candy was used as a preservative in their dried foods and mixed with leeks (wild onions) as a cough medicine and remedy for other ailments. No one is really sure just how long people have been practicing the art and science of making this wonderful product from the sap of a tree. We do know that Native Americans were already using maple sap to flavor their food long before European settlers discovered its sweetness. Indian Legend and Lore Native Americans have many wonderful stories about how they began making maple syrup. The first is the legend of Glooskap. Many, many, many years ago the Creator had made life much easier for man. In fact, in those days the maple tree was filed with syrup and all man had to do was cut a hole in the maple tree and the syrup dripped out. One day the young prince Glooskap (known by other names in other tribes) came upon a village of his people that was strangely silent. There were no dogs barking, no children playing, no women minding the cook fires, and no men getting ready to go hunting! Glooskap looked and looked and finally found everyone in the nearby maple grove . They were all lying at the bases of the trees and letting the sweet syrup drip into their mouths. Even the dogs were enjoying the syrup. “Get up, you people,” Glooskap called. “There is work to be done!” But no-one moved. Now Glooskap had special powers, and he used these powers to make a large bark container. He flew to the lake, filled the container with water and flew back to the maple grove . When he poured the water over the trees it diluted the syrup so it was no longer sweet. ”Now, get up you people! Because you have been so lazy the trees no longer hold syrup, but only sap. Now you will have to work for your syrup by boiling the sap. What’s more, the sap will soon run dry. You will only be able to make syrup in the early spring of the year!” Another legend relates to the Earth Mother, Kokomis, who made the first maple syrup. Now Kokomis made a hole in a tree, and maple syrup poured out. However, her grandson, Manabush, was worried that if the sweet gift of the maple tree was so easily obtained, the Indians might become shiftless and lazy. So he showered the top of the sugar maple with water, thus diluting the maple syrup into sap. The Chippewas and Ottawas of Michigan tell a similar story of the god NenawBozhoo, who cast a spell on the sugar maple tree many moons ago, turning the near pure syrup into what is now called sap. He did this because he loved his people and feared they would become indolent and destroy themselves if nature’s gifts were given too freely. This legend is unique in that, in various forms, it can be found almost universally throughout the Eastern Woodland Indian tribes. This is unusual for cultures that did not have a written history. Perhaps a more believable story is that of the Indian woman named Moqua. The story was recounted in the April 1896 issue of The Atlantic Monthly by Vermonter Rowland E. Robinson. The story goes that Moqua was cooking a prime cut of moose for her husband, the hunter Woksis. However, Moqua became preoccupied with her quill-work and let the pot boil dry. Realizing she did not have time to melt some snow she used some maple sap she had been saving for a beverage. Woksis was so impressed with the meal he broke the pot so he could lick the last of the “goo” from the pot shards. Yet another legend states that a chief removed his tomahawk from the trunk of a sugar maple tree, where he had thrown it the night before. As the sun got higher, the sap began to drip from the gash in the tree. The Chief's wife tasted it and discovered that it didn't taste bad, so she used it to cook the meat (though another version says that the pot was left under a broken sugar maple branch and the sap dripped into it). Later when the meat was cooked, the sap boiled down to a syrup. The irresistibly sweet scent and taste of the maple meat so delighted the Chief that he named it Sinzibuckwud—a word meaning “drawn from trees.” This became the word used most often by Native Americans when referring to maple syrup. Early Indian Methods Native Americans gradually reduced the sap to syrup by repeatedly freezing it, discarding the ice, and starting again. Some made birch bark containers that held about 20 to 30 pounds of maple sugar for storage. The Ojibways of the Great Lakes , the Wyandots of the Detroit River , and the Indians at Pidgeon Lake , were similar in how they processed the maple sap. As soon as the sap began to rise, the women and their families migrated in family groups to the maple groves, or “sugar bushes,” where they erected a camp and lived in wigwams made of bark. They prepared troughs, collected the sap, and brought it to the fire, while the most experienced women regulated the heat. Sometimes the sap was made to boil by placing hot stones in the mixture. Freshly heated stones were constantly added, while the cooler ones were fished out and reheated. Usually, each woman had her own sugar shack. Native Americans had various names for certain maple items. the Cree called the sugar maple Sisibaskwatattik (tree), the Ojubway called maple sugar Ninautik (our own tree), and other tribes called the maple, Michton. Early Native Americans seldom used salt (they preferred sugar) and used maple on meat and fish. Some tribes celebrated the return of spring with a “maple moon” festival which is know today as “sugar bush time".

Ojibwa/Chippewa

Their name also occurs as Ojibway and Chippeway, but they are not to be confused with the Chipewyan. In the mid-17th cent., when visited by Father Claude Jean Allouez, they occupied the shores of Lake Superior . They were constantly at war with the Sioux and the Fox over possession of the rich fields of wild rice in this region. When the Ojibwa received (c.1690) firearms from the French, they drove the Fox from N Wisconsin . They then turned against the Sioux, compelling them to cross the Mississippi River . The Ojibwa continued their expansion W across Minnesota and North Dakota until they reached the Turtle Mts. in N central North Dakota . This group became the Plains Ojibwa.

In 1736 the Ojibwa obtained their first foothold E of Lake Superior, and after a series of engagements with the Iroquois, they obtained the peninsula between Lake Huron and Lake Erie . Thus by the mid-18th cent. they controlled a large area from the eastern shore of Lake Huron in the east to the Turtle Mts. in the west. The Ojibwa, one of the largest tribes N of Mexico, then numbered some 25,000. They were allied with the French in the French and Indian Wars and with the British in the War of 1812. After the War of 1812 they made a treaty with the United States , and since that time they have lived on reservations in Michigan , Wisconsin , Minnesota , North Dakota , and Montana .

Traditionally the Ojibwa, except for the Plains Ojibwa, were a fairly sedentary people who depended for food on fishing, hunting (deer), farming (corn and squash), and the gathering of wild rice. They obtained and used maple sugar and smoked kinnikinnick, a tobacco made from dried leaves and bark. The characteristic dwelling was the wigwam. The Ojibwa had a unique form of picture writing that was intimately connected with the religious and magico-medical rites of the Midewiwin society.

Today the Ojibwa, or Chippewa, constitute the third largest Native American group in the United States , numbering over 100,000 in 1990. Their numerous bands include the Turtle Mountain , Sault Ste. Marie, Red Lake , Minnesota , Lac Courte Oreilles, White Earth, Leech Lake , Bad River , and others. More than 76,000 live in Canada , in 125 bands. While some Ojibwa are engaged in the traditional occupations of hunting, fishing, and harvesting wild rice, others run manufacturing and casino businesses. Some bands are still seeking redress for the loss of hunting and fishing rights stemming back to treaties made in the 1850s..

See F. Densmore, Chippewa Customs (1929, repr. 1970); R. Landes, Ojibwa Sociology (1937, repr. 1969) and Ojibwa Woman (1938, repr. 1971); H. Hickerson, The Chippewa and Their Neighbors (1970).

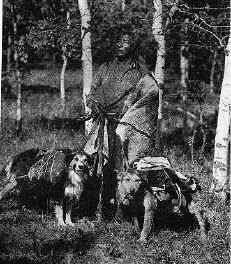

The Chippewa used dogs for hunting and to pull travois. In most tribes the women cared for, bred and trained the dogs for drags and sled pulling. The toboggan, introduced after the Conquest, soon became the universal form of winter transport form the St. Lawrence to the Mackenzie River.

THE ALASKAN REGION

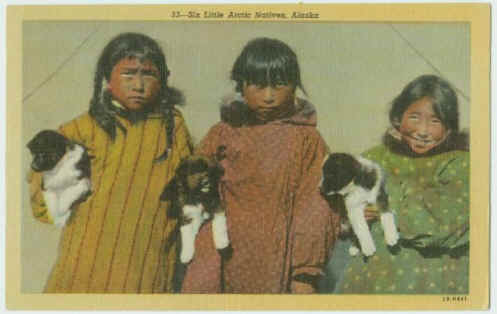

Eskimo, a general term used to refer to a number of groups inhabiting the coastline from the Bering Sea to Greenland and the Chukchi Peninsula in NE Siberia. A number of distinct groups, based on differences in patterns of resource exploitation, are commonly identified, including Siberian, St. Lawrence Island, Nunivak, Chugach, Nunamiut, North Alaskan, Mackenzie, Copper, Caribou, Netsilik, Iglulik, Baffinland, Labrador, Coastal Labrador, Polar, and East and West Greenland. Since the 1970s Eskimo groups in Canada and Greenland have adopted the name Inuit, although the term has not taken hold in Alaska or Siberia. In spite of regional differences, Eskimo groups are surprisingly uniform in language, physical type, and culture, and, as a group, are distinct in these traits from all neighbors. Their antiquity is unknown, but it is generally agreed that they were relatively recent migrants to the Americas from NE Asia, spreading from west to east over the course of the past 5,000 years.

Eskimo Life

Traditionally, most groups relied on sea mammals for food, illumination, cooking oil, tools, and weapons. Fish and caribou were next in importance in their economy. The practice of eating raw meat, disapproved of by their Native American neighbors, saved scarce fuel and provided their limited diet with essential nutritional elements that cooking would destroy. Except for the Caribou Eskimo of central Canada, they were a littoral people who roved inland in the summer for freshwater fishing and game hunting.

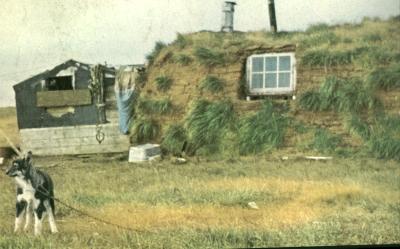

Eskimos traditionally used various types of houses. Tents of caribou skins or sealskins provided adequate summer dwellings; in colder seasons shelter was constructed of sod, driftwood, or sometimes stone, placed over excavated floors. Among some Eskimo groups the snow hut (igloo) was used as a winter residence. More commonly, however, such structures were used as temporary overnight shelters during journeys. The dogsled was used for the hauling of heavy loads over long distances, made necessary by the Eskimos' nomadic hunting life. Their skin canoe, known as a kayak, is one of the most highly maneuverable small craft ever constructed. Hunting technologies included several types of harpoons, the bow and arrow, knives, and fish spears and weirs. While iron and guns have come into common use in the 20th cent., previously weapons were crafted from ivory, bone, copper, or stone. Their clothing was sewn largely of caribou hide and included parkas, breeches, mittens, snow goggles, and boots. Finely crafted items such as needles, combs, awls, figurines, and decorative carvings on weapons were executed with the rotary bow drill.

Eskimo Culture

Particularly when compared to other hunting and gathering populations, Eskimo groups were justly famous for elaborate technologies, artisanship, and well-developed art. They lived in small bands, in voluntary association under a leader recognized for his ability to provide for the group. Only the most personal property was considered private; any equipment reverted through disuse to those who had need for it. In the traditional Eskimo economy, the division of labor between the sexes was strict; men constructed homes and hunted, and women took care of the homes. Their religion was imbued with a rich mythology, and shamanism was practiced.

Contemporary Life

Eskimos in the United States and Canada now live largely in settled communities, working for wages and using guns for hunting. Their mode of transportation is typically the all-terrain vehicle or the snowmobile. The native food supply has been reduced through the use of firearms, but, as a result of increased contact with other cultures, the Eskimo are no longer completely dependent on their traditional sources of sustenance. The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971 granted Alaska natives some 44 million acres of land and established native village and regional corporations to encourage economic growth. In 1990 the Eskimo population of the United States was some 57,000, with most living in Alaska. There are over 33,000 Inuit in Canada, the majority living in Nunavut, the Northwest Territories, N Quebec, and Labrador. In 1999 a separate, predominantly Inuit territory, Nunavut, was created out of the Northwest Territories. There are also Eskimo populations in Greenland and Siberia .

See U. Steltzer, Inuit: The North in Transition (1985); A. Balikci, The Netsilik Eskimo (1989).

The 14 divisions of the Tlingit may reflect a former era when they were entirely independent tribes. Important among the divisions are the Chilkat, the Yakutat, the Stikine, the Sitka, the Auk, and the Huna. In 1741, when visited by Aleksei Chirikov and Vitus Bering, the Tlingit lived in SE Alaska , along the coast and on the islands around Sitka, S to Prince of Wales Island and N to the Copper River. The Russians built (1799) a fort near the site of Sitka, but the indigenous inhabitants drove them out. Aleksandr Baranov, however, later captured the fort, killing many native people. He established a trading post there, which grew into Sitka. There was constant strife between the Tlingit and the Russians in the early 19th cent. In 1990 there were about 14,400 Tlingit in the United States, mostly in native villages in Alaska. Around 1,200 live on reserves in British Columbia and the Yukon Territory. Tlingit culture, like that of the Haida and the Tsimshian, was typical of the Northwest Coast area. Some of their finely carved totem poles survive, and the Tlingit still carry on many of their traditional dances. The name is also spelled Tlinget, Tlinkit, and Tlinket.

See L. Jones, A Study of the Tlingets of Alaska (1914, repr. 1970); T. M. Durlach, The Relationship Systems of the Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian (1928, repr. 1974); R. L. Olsen, Social Structure and Social Life of the Tlingit in Alaska (1967); F. De Laguna, Under Mount Saint Elias (1972).

The Hare, a Déné tribe which shares with the Loucheux the distinction of being the northernmost Natives in America , their habitat being immediately south of that of the Eskimos. Their territory extends from Fort Norman, on the Mackenzie, west of Great Bear Lake, to the confines of the Eskimos, not far from the Arctic Ocean. They are divided into five bands or sub-tribes, namely: the Nni-o'tinné, or "People of the Moss", who rove along the outlet of Great Bear Lake; the Kra-tha-go'tinné or "People among the Hares", who dwell on the same stream; the Kra-cho-go'tinne, "People of the Big Hares", whose hunting grounds are inland, between the Mackenzie and the coast of the Arctic Ocean; the Sa-cho-thu-go'tinné, "People of Great Bear Lake", whose name betrays their location, and lastly, the Nne-lla-go'tinné, "People of the End of the World", whose district is conterminous with that of the Eskimos. The Hares do not now number more than 600 souls. They are a timorous and kindly disposed set of people, whose innate gentleness long made them and their hunting grounds, bleak and desolate as they are, a fair field for exploitation by their bolder neighbours in the West and South-East. According to some this natural timidity is responsible for their name; but others apparently better informed contend that it is derived from the large number of arctic hares (lepus arcticus) to be found in their country, and the aboriginal designations of some of their ethnic divisions confirms this opinion. Their medicine men, or shamans, were formerly an object of dread to the sub-arctic Dénés, being famous for the effectiveness of their ministrations and the wonderfulness of their tricks.

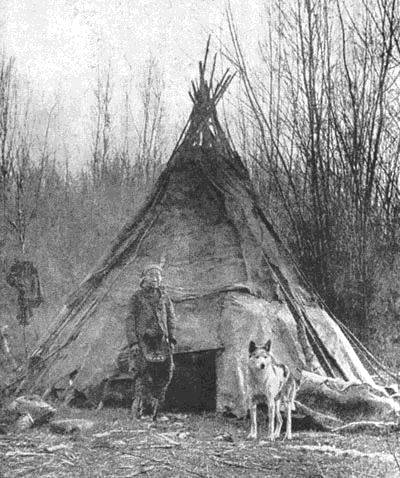

Tlingit Indian houses, found in the Southeast coastal regions of Alaska, were used for smoking and drying fish. Dogs were domesticated in the New World about 10,000 years ago. Evidence has been found of their use in the arctic nearly 4,000 years ago. Dogs probably were first domesticated for warning and defense rather than for transportation or food.

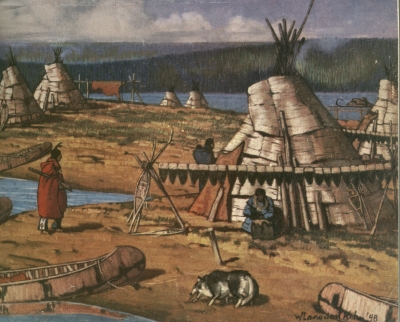

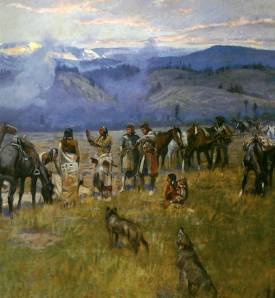

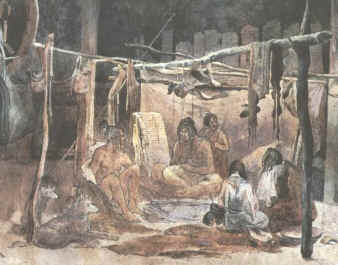

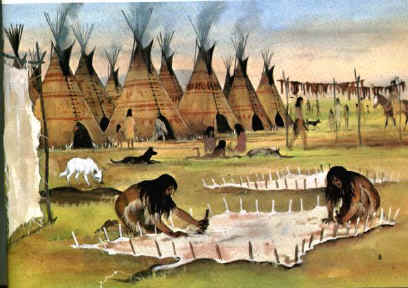

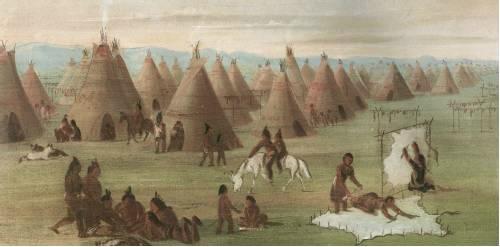

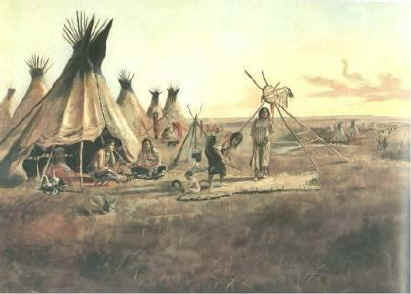

The Silk Robe Charles Russell circa 1890 Two women prepare a buffalo skin for tanning. An especially fine buffalo robe required ten days of steady labor. It was called a "silk robe" because of the softness of the leather and the sheen of the fur. Note the dog travois and the sleeping Indian dog, who undoubtedly pulled the buffalo hide while hooked to the travois.

|

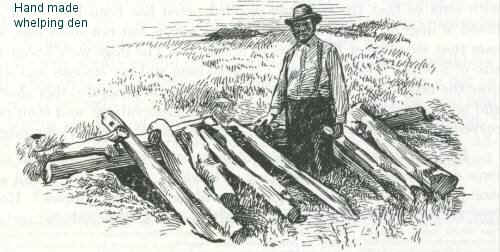

THE HIDATSA LOVED THIER DOGS AND CARED FOR THEM A GREAT DEAL.

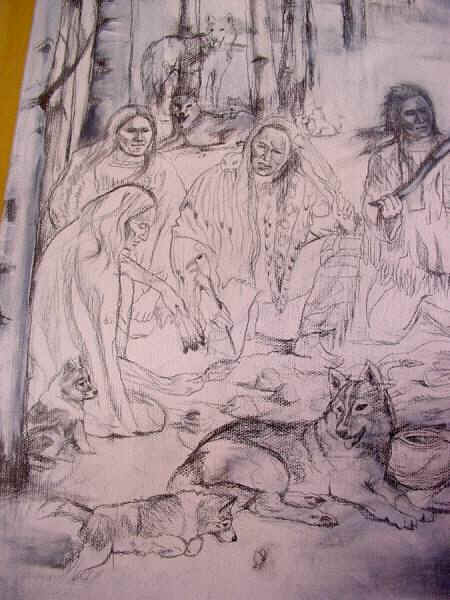

HERE WITH A DRAWING DONE BY WOLF CHIEF, BUFFALO BIRD WOMAN'S SON, DEPICTS A WHELPING DEN MADE FOR THE FEMALE DOG FOR HER TO HAVE HER PUPS IN. THE MEN WOULD DIG A LARGE HOLE, COVERING IT WITH LOGS AND THEN BRANCHES FOR THE FEMALE TO WHELP HER PUPS IN.

|

|

|

THEN AND NOW

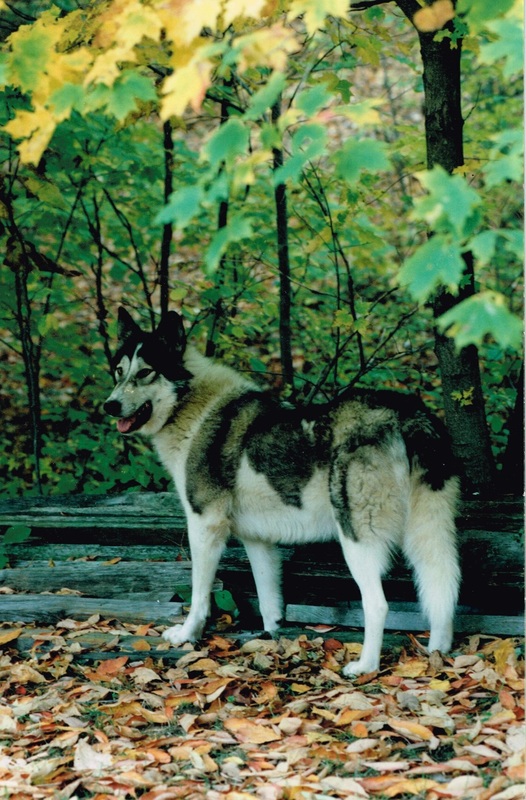

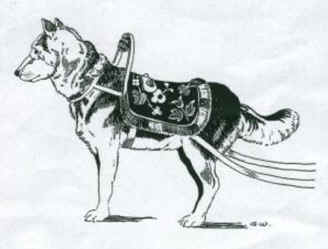

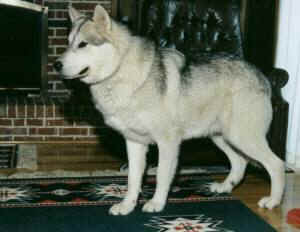

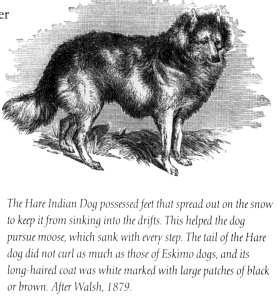

BELOW ARE PHOTOGRAPHS OR DRAWINGS OF NATIVE AMERICAN DOGS FROM ONE HUNDRED TWENTY FIVE YEARS AGO OR MORE. COMPARED WITH MODERN NATIVE AMERICAN DOGS

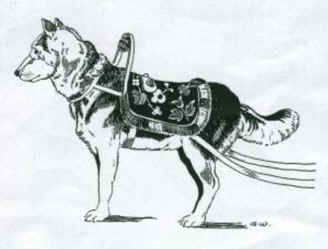

A "HARE" INDIAN DOG. ORIGINATING FROM THE NORTH EASTERN PART OF ALASKA AND THE YUKON TERRITORY OF CANADA. DRAWING CIRCA 1830'S

lithograph by John Woodhouse Audubon, the son of John James Audubon. The dog in the picture is an actual breed of dog that the Hare Indians from Canada used as hunting dogs. They were more domestic than wolves but could only be trained for hunting. They were known to be affectionate with people but did not like to be confined.

|

The Hare Indian Dog was bred and raised for hunting by the Indians North of the Great Lakes Westward to the Rockies. The Hare Indians, the Assiniboine and the Nez Perce were several of the nations that raised broken patterned or spotted colored dogs. These sketch was drawn in the 1830’s by John Richards during his study of the Northwestern McKenzie District, Canada.

|